They may never have graced the group stages of the UEFA Champions League, but Dinamo Tbilisi remain an iconic name for football devotees old enough to remember a time before shirt sponsors or the back-pass rule. Georgia’s establishment team engraved their place in the continent’s annuls of the beautiful game in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when a fast, mobile and technical team swept aside Europe’s best, carrying a fearsome and mysterious reputation west of the Berlin Wall.

Their triumph in the 1981 European Cup Winners’ Cup continues to be a source of pride for the city and the country as fathers, uncles and grandfathers regale the typically vast family table with tales of Georgian football’s finest ensemble. But 33 years on, a younger generation of Tbiliselebi are growing tired of toasting a glass of Saperavi (a revered type of Georgian red wine) to a team they never saw. They want their own European adventures with which to grow old.

The legendary Dinamo Tbilisi team of 1981, European Cup Winners’ Cup winners

And this year, hopes are high that the now 15-time Georgian champions can recapture their former fame, and re-emerge from the rusting post-Soviet mire in which they have been wallowing for some time.

Michal Bilek – Dinamo’s Latest Czech Mate

The 2013-14 season saw Dinamo consolidate their place at the lonely, jagged peak of Georgia’s football pyramid. On a comfortable cruise to a domestic double, the club lost Czech head coach Dusan Uhrin Jr. to Viktoria Plzen in December. Such was their dominance though, that Dinamo could afford to wait to appoint a full-time successor until summer where the number of available coaches would be higher.

Youth coach Malkhaz Zhvania took interim charge and despite nearest challengers Zestafoni winning 12 of their last 14 league games, and having to play the Georgian Cup final against Chikhura Sachkhere with ten men for 70 minutes, the caretaker sealed both pieces of silverware before being inevitably nudged aside.

On June 2, exactly two weeks after the Cup final, the former Czech Republic head coach Michal Bilek was announced as Zhvania’s replacement by the club’s chairman, Roman Pipia, a Georgian businessman with strong Russian connections who took over the club in 2011.

“Europa League – minimum” – Michal Bilek, Dinamo Tbilisi head coach

At Bilek’s unveiling, Pipia was not entirely convincing when forecasting a better future for Dinamo under the Czech. The Dinamo chairman said: “We chose Bilek and time will tell if our decision was right. I think we will see Dinamo progress because Bilek can mobilise the club.”

Before Pipia had time to explain exactly what mobilisation he was referring to, the pack of Georgian journalists moved on to scrutinise the length of the Czech’s contract. Bilek had been handed a not particularly confidence-inspiring one-year deal. The questions were no doubt inspired by Pipia’s propensity for impatience with coaches. In January 2012, he sacked head coach Alex Garcia during the winter break, two weeks after assuring the Spaniard that his job was safe until the summer.

Pipia retorted: “Perhaps, this (one year contract) gives more motivation to a coach.” The Georgian businessman then added, perhaps ominously for Bilek: “Dinamo is not a club where even high class coaches can work easily. We have to work hard to make it through to the group stage of the Champions League every year.”

This is an ambitious goal. Not only have Dinamo never played in the group stage, the club have never won more than one qualifying round since the European Cup was rebranded as the Champions League in 1992.

While the former Czechoslovakia and Real Betis midfielder concurred that the Champions League group stage should be the aim, he labeled that the best case scenario. Succinctly, Bilek made clear his goal for the Georgian side: “Maximum – group stage of the Champions League. Minimum – Europa League.”

Mission Improbable – The Long Road to the Champions League

That statement means that Bilek’s first competitive match for Dinamo is a pivotal one for him as the Georgian champions face energy rich FK Aktobe of Kazakhstan in the second qualifying round of the Champions League.

To reach the group stage, steering Dinamo to victory over the Kazakh champions, not an easy accomplishment as Celtic will testify after last year’s close shave with Shakhter Karagandy (Read Futbolgrad’s article Shakhter Karagandy – A Steppe Away from the Champions League), would be only the first of three wins needed.

Dinamo were drawn to face Kazakhstan’s FK Aktobe in the 2nd Qualifying Round

Indeed, failure to overcome FK Aktobe, for whom the Georgian-named Uzbek international of Turkish descent Timur Kapadze is a key midfielder, would see Dinamo plunge out of Europe altogether as the dubious Europa League safety net is not laid out until the following round.

The recent division of qualifying into champions and non-champions spares Dinamo the prospect of an English, German or Spanish giant in subsequent qualifying rounds. However, the Georgians will likely have to defeat at least one of Celtic, Red Bull Salzburg, their conquerors of last season Steaua Bucharest or Bilek’s old club Sparta Prague to realise Pipia’s grand vision.

The rewards for doing so could be life-changing for Dinamo. Reaching the play-off round (which would be the third and final hurdle for Dinamo) yields a bonus of 2.1 million Euros, and a place in the group stage earns a base fee of 8.6 million Euros.

The commercial, TV-oriented nature of the Champions League means that clubs are allocated a further share of the pot according to the relevant country’s so-called “market pool” rendering the likely share of a Georgian club low. Even then, the lowest prize money of any team in season 2013-14 was Viktoria Plzen, now coached by Bilek’s predecessor, who took in 11.1 million Euros.

Aside from the official prize money, there would be other financial rewards. Dinamo struggles to generate revenue in the Umaglesi Liga (Georgian Premier League) where crowds rarely creep over the 1,000 mark despite entry being free for the bulk of matches.

A deserted Dinamo Arena for a league fixture against Sioni Bolnisi, February 2014

However, with a nation of football fanatics starved of top-level action, the Georgian champions would be guaranteed three full houses at the 54,000-seater Dinamo Arena for their home matches in the group stage, regardless of ticket prices thereby adding, hypothetically at this moment, another significant boost in revenue.

To illustrate just how significant these riches could be to the club, their current top earner is the 33-year old Spanish forward Xisco who is on roughly 20,000 Euros per month. The rest of the squad earn no more than half of that which – although still a very high salary in Georgia where the average is less than 500 Euros – drastically limits the club’s potential to improve the squad.

In transfer dealings, Dinamo shop at the flea market rather than the high street. The lowly reputation of the Umaglesi Liga makes moving to Dinamo a tough sell. This summer, an attempt to bring Georgian winger Sandro Kobakhidze back home from the wilderness of Dnipro’s reserves was trumped by an offer from Ukrainian strugglers Volyn Lutsk.

But potentially club-changing money aside, a place in the Champions League group stage would offer a new generation the European nights of which they have long been deprived.

The Dusseldorf Dynasty – Dinamo’s Greatest Day

When Bilek entered the Dinamo Arena for the first time he would have observed quickly the close connection Dinamo retains with the achievements of Georgian football past. The walls of the Press Center and VIP Lounge are awash with pictures of Dinamo’s two great sides.

First, the 1964 “Golden Boys”. Described by France Football magazine as “the best Eastern representatives of South American football traditions” this lauded Dinamo team included stars of the 1960 European Championships-winning USSR squad Slava Metreveli and Mikheil Meskhi. They beat Torpedo Moscow 4-1 in the Uzbek capital Tashkent in a play-off to win the club’s first ever Soviet Top League title but were denied the opportunity to play in European competition as Soviet clubs did not enter until 1965.

Dinamo Tbilisi 3-0 Liverpool (Gutsaev, Shengelia, Chivadze)

Dinamo’s second wave of excellence came in the late 1970s and early 1980s under manager Nodar Akhalkatsi. Their second USSR title in 1978 earned the Georgian club a place in the 1979-80 European Cup First Round where they destroyed Liverpool 3-0 in Tbilisi in front of a crowd that, depending on who you speak to and how much wine has been consumed, can reach anything up to 120,000.

Malkhaz “Fatso” Norakidze, the club’s historian and stadium events coordinator was a 26-year old metal work student at the time, whose nickname seems a touch undeserved amongst Georgia’s omni-plump male population. In his treasure trove of an office, the walls layered with memorabilia, he fondly recalls: “We were confident against Liverpool. With our forward line, anyone was beatable.”

The Daily Telegraph reported that the Georgians created “a vociferous and intimidating crowd reminiscent of Anfield itself” with “Fatso” laughing as he recalled the hours leading up to the game: “People could have sold tickets to the black market for a hundred times their face value. But nobody did. No-one was missing this match.”

A story from another long-time Dinamo follower Temur, 61, who had started working for the Ministry of Finance days before the game, highlights how coveted a match ticket was. “I got one ticket from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Then, a few days before the game I met one of Dinamo’s coaches at a supra (traditional Georgian feast) and he gave me another. I gave it to a friend who was so grateful that he paid to take me to restaurants and bars for a week.”

Despite the alleged crowd being some 40,000 over capacity, the harshly nicknamed historian Norakidze rebuffs the suggestion that it might have been dangerous. He explained: “Back then, people behaved better. They were scared of the police. There were black buses outside the stadium. If anyone misbehaved, they would be put in the bus and driven outside the city until the game finished.”

Malkhaz “Fatso” Norakidze, Dinamo Tbilisi club historian enjoys a stroll down memory lane

In the Soviet era, Dinamo Tbilisi were perceived as the national team of Georgia, and supported by the country’s people accordingly – this story was familiar across the post-Soviet space with the likes of Ararat Yerevan (Armenia), Zalgiris Vilnius (Lithuania) and Pakhtakor (Uzbekistan) similar examples. Indeed, the Soviet statistics department held that there was a direct link between Dinamo winning and general work productivity. As “Fatso” philosophically put it: “Usually, the tea lady works with one hand. But when Dinamo won, the next day she worked with two.”

Defeat to Hamburg followed but in 1980-81 having won the Soviet Cup, Dinamo competed gloriously in the European Cup Winners’ Cup. Having dismantled West Ham 4-1 at Upton Park in the quarter-final, the home crowd stood to applaud Dinamo off the park.

West Ham fanzine “They Fly so High” wrote in a report that irksomely referred to the all-Georgian team as “the Russians” that “the Soviet masters taught us a lesson” and that Dinamo had “waltzed and weaved magical moves to shatter West Ham’s dreams.”

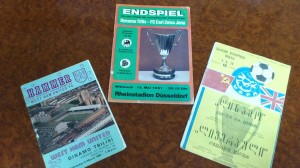

Norakidze’s Prized Programmes (left to right) – West Ham (away) 1981, Carl-Zeiss Jena Cup Winners’ Cup final 1981, Liverpool (home) 1979.

The East London club’s manager at the time, the late John Lyall, claimed Dinamo had “everything you could admire in a side” and after the second leg (which West Ham won 1-0) he believed the Hammers were knocked out by “one of the best teams in the world.”

A semi-final triumph over Feyenoord handed Dinamo a final against East Germans Carl Zeiss Jena in Dusseldorf, West Germany. In front of a crowd officially posted as 9,000 (believed to be less than 5,000) the Georgians came from behind to win 2-1, with Abkhazian midfielder Vitaly Daraselia, who died the following year in a car crash, scoring the winner.

Other famous names in that storied Dinamo team were Ramaz Shengelia, whose goal for USSR effectively knocked Scotland out of the 1982 World Cup, and David Kipiani, an attacking midfielder retrospectively referred to as “the Georgian Zidane”, after whom the Georgian Cup trophy was named following his death in 2001.

Dinamo should have played in the Super Cup but were denied the opportunity to do so as would-be opponents Liverpool claimed the match (then played over two legs) could not be accommodated in their schedule. Naturally, Georgians claim to this day that this was not the case. Dinamo historian Norakidze claimed: “they were shitting themselves about playing us again”.

Modest Aims for Modern Dinamo

These memories are increasingly hazy now, and no English club would fear playing against Dinamo today, as was evidenced by Tottenham Hostpur’s 8-0 aggregate crushing of the Georgian champions in the Europa League play-off round last season.

Today’s goal though is not to topple Western Europe’s elite clubs but rather to simply sit alongside them and eat from the same bountiful trough.

Local sports journalist and TV comedian Gocha Tandarashvili was less than three years old for the 1981 triumph but he outlines the importance of a revived Dinamo to the younger generations. He notes: “Today, kids in Georgia walk around the streets in the shirts of foreign clubs and countries. If we (Dinamo) can get to the group stage, people will believe in Georgian football again.”

Dinamo Here and Now. Foreground: Bilek’s Summer Signings; Background: Photos of Storied Dinamo teams of yesteryear

However, Bilek’s ability to lead Dinamo there is handicapped by a lean playing staff from which to pick. There are a handful of Georgian internationals in the squad but only goalkeeper Giorgi Loria is an established starter. Georgia may be fiercely patriotic but its best footballers are to be found miles from home, in the Dutch, Russian, or Ukrainian leagues among others.

Strengthening the Dinamo squad has proved a difficult task for Bilek with two fellow Czechs Radek Dosoudil (31) and Mario Licka (32), and estranged Spaniards Rafa Jorda and Rafa Garcia the sum of Dinamo’s international arrivals this summer.

Bilek trains his new, largely inherited Dinamo side

Nevertheless, Dinamo’s preparations have been those of a club with lofty aspirations as Bilek’s squad have spent a large part of pre-season at a state-of-the-art training facility in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, Dinamo’s impressive new academy was opened in 2013 by Cristiano Ronaldo among others.

The heritage, the intentions, the image and the infrastructure all suggest that Dinamo can return to European football’s top table and Bilek has already shown that he can achieve success with limited playing resources.

Guiding a Czech Republic squad bereft of outfield quality to the Euro 2012 quarter-final is the standout example of doing so in his career to date. But even that achievement would be surpassed if he can navigate Dinamo back to its once proud place among the European heavyweights.

Alastair Watt is a published sports journalist whose interest in the east was spawned at the age of 7, watching his native Scotland wallop the CIS at Euro 92. Fifteen years later he had his first taste of football beyond the old iron curtain, in a visit to Dnepropetrovsk (Ukraine) to see his beloved Aberdeen smash and grab an away goals triumph in the UEFA Cup. Whether it was the Stalinist architecture, the plentiful Pelmeni, or the vodka, further venturing to the post-Soviet Space soon became obsessively frequent before moving to Tbilisi (Georgia) in 2010 where he remains. You can follow Alastair on Twitter @Tbilisidon

Futbolgrad on 14 July, 2014